Namibia image by Heribert Bechen licensed using Creative Commons

Glasses for the masses - John Friedman

Anthropologist John Friedman (Darwin 1998) describes how field work opened his eyes to the implications of visual impairment in low income countries. Today he’s part of a charity working to help close the visual divide.

What would my life look like if I had been born and raised in Kaokoland, where there are no opticians, and no eye glasses?

When I began my studies as a severely myopic doctoral candidate in the Department of Social Anthropology, I envisioned a future academic career as a university professor, as teacher and researcher. I went on to achieve that ambition and now, nearly fifteen years on, I remain one of the resident anthropologists at Utrecht University’s honours college, University College Roosevelt, in The Netherlands. What I didn’t at all anticipate, however, was that my doctoral research on political imagination and the post-apartheid state in southern Africa would eventually lead me toward the field of global eye health, optometry and, of all things, optics.

As part of my DPhil requirements I was obliged, like all social anthropologists, to undertake an extensive period of fieldwork in support of my research project. Following two years of coursework and supervision in Cambridge, I moved to a small town in northwest Namibia, near the Angolan border, where I lived for the next 15 months. Considered one of the remotest parts of the country, Kaokoland is known for its beautiful and barren landscapes, and for the semi-nomadic pastoralists who reside there.

An eye-opening experience

As an American, and now European, I have never had much of an issue correcting my otherwise disabling visual impairment. I began wearing contact lenses at the age of twelve, and thereafter had no further need for glasses, that is, until I began my fieldwork some two decades later. Kaokoland is a dusty and dry part of an already arid country, and, soon after my arrival there, intense eye irritation forced me to set aside my contact lenses in exchange for a pair of new glasses, which I acquired at the nearest optician’s shop… 550 kilometres away!

The experience opened my eyes in more ways than one. I began to realise, for example, that hardly any of the people living in Kaokoland were wearing glasses. Was this because they didn’t need them, or because they couldn’t access them? Furthermore, I understood suddenly the extent to which my life would have been completely different had it not been for that simple, concave lens that enables me to see, and live in, the world around me. What would my life look like if I had been born and raised in Kaokoland, where there are no opticians, and no eye glasses?

Implications of visual impairment

The high incidence of uncorrected refractive error, otherwise known as short- and far-sightedness, is not limited to the people of northwest Namibia, not by a long shot. Some estimates suggest that 2.5 billion people require, but cannot acquire, a pair of eye glasses. More than 90 percent of them live in low- and middle-income countries where there are hardly any eye health professionals, especially in rural areas. For those that can reach the eye doctor, the high cost of glasses presents another major obstacle.

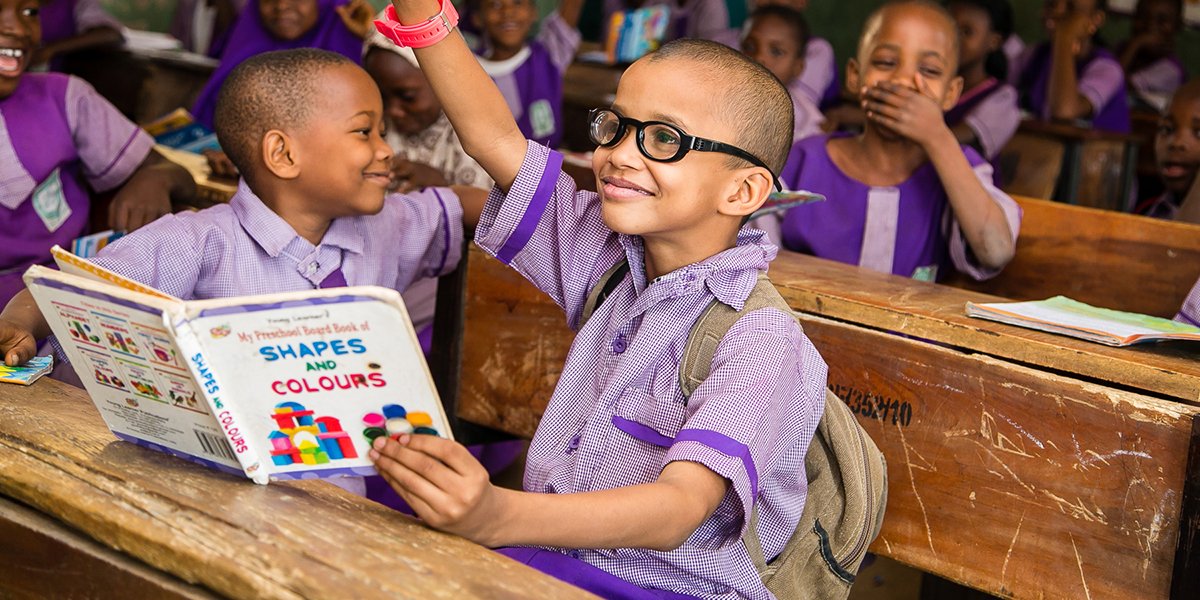

The implications of this silent epidemic, for both the individuals affected and the world as a whole, are quite staggering. Children who cannot see clearly do not achieve their learning potential; recent studies show that the provision of glasses to children improves learning by 33-50% per year. Those with glasses learn more, stay in school longer and increase their chances for a productive and healthy life. Similarly, adults who do not see clearly do not achieve their economic potential. Clear vision increases people’s earnings, and increased earnings reduces poverty. In fact, uncorrected visual impairment costs the developing world economies more than $400 million per annum.

An innovative vision

Seven years after having earned my degree at Cambridge, and already well into my teaching career in the Netherlands, I finally published my monograph on people and the state in northwest Namibia, Imagining the Post-Apartheid State: An Ethnographic Account of Namibia (2011, Berghahn). Shortly around that time, I also learned about an innovative strategy to try and address the problem of uncorrected visual impairment. What if we could design and mass produce a pair of glasses that did not require a trained eye doctor to prescribe, and that could be so inexpensive to produce that even the world’s poorest people could afford a pair?

Recollecting my own experiences in Kaokoland, and finding myself ready to embark upon a new research project, I decided to join a team of optical physicists, production engineers, designers, optometrists and global health specialists to work on the idea. To my surprise, I felt quite comfortable working so far outside my original field of formal training. Even though I hadn’t realised it at the time, many of the everyday interactions I had at Cambridge – sitting beside a physicist at a formal hall, listening to one of those fantastic Darwin Lectures, talking in the pub with friends who were undertaking research in other university departments – had prepared me well for such a diverse intellectual and professional space.

The 20/20 project

And now, five years later, our 20/20 project – a consortium made up of an NGO, a charitable foundation and a social enterprise – is mass producing and distributing the FocusSpec adjustable focus glasses, and is working to develop even newer technologies to help close the visual divide. Our FocusSpecs correct approximately 90% of all refractive errors by utilising an optical technology that allows one to easily alter the strength of the lens through the simple turn of a dial, not so unlike a pair of binoculars. In addition, its ease of use means that a lay person can be trained quickly to perform vision screening for others, and instruct them in the self-adjustment and fitting of the spectacles. Currently, a pair of FocusSpecs can be produced for a very reasonable price, but we hope that as the project scales we will be able to supply a pair of glasses for less than a pint of beer.

To date, our project has distributed more than 100,000 pairs of glasses to people in more than 50 countries. But given the scope of the problem globally, we are not yet able to make even a dent in relation to the need. For this reason, we are trying to partner with as many other organisations and people as possible. Our central question is no longer how to design or produce such glasses but rather ‘how can we distribute one million glasses per year?’ And this is shaping up to be an even greater challenge.

John Friedman has an MPhil and DPhil in Social Anthropology and attended Darwin College. He is Associate Professor of Sociocultural Anthropology and Development at University College Roosevelt, Utrecht University, and co-founder of The 20/20 Project in Antwerp, Belgium. He can be contacted at john@the2020project.info