Models Triptych: Madonna Cascade

Rose Garrard, 1982

Donated by the artist, 1992

© Rose Garrard

Art without men

The Women’s Art Collection, held at Murray Edwards, is Europe’s largest collection of art by women. Here is the world through women’s eyes.

The woman in the picture wears a dark dress with a simple white cap and a ruff, the clothing of Dutch Renaissance paintings. Holding a palette, she is typical of an artist of that Golden Age movement, even though she would become mostly forgotten after her death. Meet Judith Leyster, shown here in a copy of her self-portrait done by the artist Rose Garrard in 1982.

But Garrard’s artwork goes further, gets messier. The painting is incomplete and the frame, featuring plaster casts of the Virgin and child, has melted away, arcing in a stalactite to the floor, echoing the curve of the surrounding staircase. In the negative space created you can see the fabric of the building of Murray Edwards College.

“Garrard is very interested in frames, frames that break and frames that fall off the wall,” says Harriet Loffler, Curator of The Women’s Art Collection at the College. “I feel that she talks about the frames, the boundaries, that women have to break through, both politically and socially, to take up space in the world. So this piece shows the work of Rose Garrard, the work of Judith Leyster and beyond that you can see the real bricks and mortar of the College, a support structure for women artists across the generations.”

For more than 40 years, Murray Edwards, formerly New Hall, has been supporting women artists in a very tangible way. The Women’s Art Collection is the biggest group of works by female painters, sculptors, photographers and performance artists in Europe. There are more than 600 works, including pieces by Barbara Hepworth, Tracey Emin and Cindy Sherman, and the vast majority is on permanent display within the College building. Most of the pieces in the collection have been donated and the public can visit the collection for free.

“What I love about the collection is that there are so many different stories, so many different points of view,” says Katy Hessel, author of The Story of Art Without Men and a Visiting Fellow at Murray Edwards. “It’s this incredible communion of women, all at different stages of their lives and with different experiences. And those experiences are ones that don’t often get spotlighted in museums and galleries.”

For Hessel, the experience of the artist Mary Husted is particularly powerful. When 17-year-old Mary became pregnant in 1962, she was sent away by her horrified family to “avoid the shame and loss of reputation”. Giving birth to her son Luke, without family support in a secluded nursing home, she resisted staff who wanted to take him away immediately and was able to spend a few precious days with her child. She watched him carefully, using her art to create sketches – his arms raised in sleep, his hairline, his cheek – before he was removed from her.

Nearly 30 years later, Husted created an artwork using the drawings of her lost son, calling it Dreams, Oracles, Icons. The piece was donated to The Women’s Art Collection, and hung on the College’s walls where, incredibly, her son came to see it. Mother and son reunited, through art.

Dream, Oracles, Icons

Mary Husted, 1991

Donated by the artist, 1992

© Mary Husted

“What’s heartbreaking about these sketches is that it’s a mother who knows what the outcome is going to be. She’s holding on with every single mark,” says Hessel. “But these artworks show so much more than just motherhood. They also show the history of what women went through to exist, how they felt shamed and what they had to give up, and how their lives were affected by people making decisions for them.”

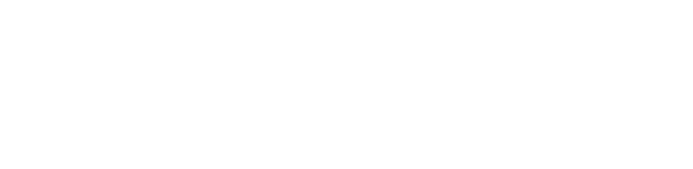

The Women’s Art Collection was founded in 1991, at a time when female artists were starting to shout more frequently and more loudly about under-representation. Indeed, the collection holds a 1989 poster made by The Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous group of feminists, female artists, which asks: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?”, pointing out that only 5% of the modern art collection was created by women, but 85% of the nudes were female.

Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?

Guerrilla Girls, 1989

Donated by the artists, 2016

© Guerrilla Girls. Courtesy guerrillagirls.com

In 1985, working in collaboration with the gallery, Kettle’s Yard, the College invited American conceptual artist Mary Kelly to take up a residency. Kelly was a controversial figure at the time, having displayed her infant son’s used nappies as part of her 1976 work Post-Partum Document.

“Kelly is a feminist, conceptual and rigorous artist,” says Loffler. “But Post-Partum Document sent the tabloid press crazy – they were outraged for its inclusion of dirty nappies. As a result, Kelly achieved a kind of iconic status. It really shows how bold Valerie Pearl, who was the College President then, and others were being in selecting her.”

Pearl continued to build on the idea of creating a space for women’s art. In 1991, working with curator Ann Jones, together with several fellows from the College, she sent out letters to a number of women artists asking them to donate work. “I think they expected perhaps around 10 people to respond,” says Loffler. Instead, nearly everyone said yes, and within a year-and-a-half, 70 pieces were donated.

As it has grown, The Women’s Art Collection has become a snapshot of women artists in the modern era – an alternative pantheon, showing the wide range of expressions in terms of both medium and theme. “Art historian Professor Griselda Pollock makes the point that women artists have always existed, but they were actively written out of art history by the male art historian in the 20th century,” says Loffler. The Women’s Art Collection, with its breadth and web-like connectivity, is a rebuttal to this linear and patriarchal canon.

And the setting is important. The Murray Edwards building is atypical for a Cambridge College. It was designed by the celebrated mid-century architectural practice Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, best known for creating the Barbican complex in London. “It’s brutalist,” says Hessel. “It’s not built in a classical or neo-classical likeness. It’s not what we all think about when we think of a civic building. The National Gallery and the British Museum, for example, promote a style of architecture imbued with a patriarchal history, and I like that The Women’s Art Collection doesn’t have that.”

She points out that the galleries, student spaces and College rooms are connected by gardens and water. “There’s a fluidity, it’s a very primal thing.” The Barbara Hepworth sculpture Ascending Form (Gloria) is sited in the gardens and, whatever the artist’s intentions may have been the shape is undeniably vulval. “Let’s say it feels inherently female,” says Hessel.

Ascending Form (Gloria)

Barbara Hepworth, 1958

On loan from the Trustees of the Hepworth Estate since 2003

Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

The interconnected, modernist building; the public access; students wandering past works by great artists as part of their everyday lives; a garden where, as Loffler points out, you can both walk on the grass and pick the flowers: all of these things demonstrate a flattening of hierarchies, and the same ethos is reflected in the collection.

“It’s important for me that there’s an equality of display, that we tune into the artists that we don’t recognise as much as those we do,” says Loffler. “It’s always been an intergenerational collection with artists recommending other artists to donate. The collection speaks of the network between those artists. Many collections are accumulated by a single individual, most likely a wealthy man, assembled and then donated for posterity. We don’t have that. We are networked, distributed. The collection naturally displaces any sort of power dynamic.”

That the collection has grown to its current size largely from donations demonstrates that the need for representation is still felt by living artists. The most recent Women Artists Market Report from the collector-focused website Artsy found that of the $11bn (£8.6bn) created by selling art at auction, only $1bn (£800m) came from the sale of work by female practitioners. Of the top 100 works, just two were by women artists: Georgia O’Keeffe and Louise Bourgeois. And while the Burns-Halpern report, produced each year by the Freelands Foundation, showed that more than half of solo shows in London in 2021 were by female artists, there were still barriers at major institutions. Only 36% of the works acquired by the Tate in that year were by women, despite just 37% of the artists in the contemporary collection being women and only 5% in the historic collection.

“Why does The Women’s Art Collection exist?” says Hessel. “The only reason it exists is because museum collections haven’t taken the effort to really look outside for different stories, different perspectives.” Within Murray Edwards, those stories have found a place on the inside.

The Women’s Art Collection is open to the public daily from 10am to 6pm and is free to visit. See the Collection's website for more information

CAM

CAM