Archaeology as a tool for today —Anastasia Christophilopoulou

Dr Anastasia Christophilopoulou (St John's 2003) began life as a gymnast, and sought a career that shared similar elements of physicality. Now, she is a classical archaeologist and curator of the new Islanders exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

She tells us about why archaeology is relevant to a post-Brexit Britain, and the power of collaboration and inclusivity.

"It's actually an interesting story..." Anastasia smiles, as I ask her how she became a classical archaeologist.

"From a young age, I was passionate about training in a profession with a physical element to it. I wanted to do something where I could work with my hands and with my body."

Born in Greece, as a young adult Anastasia was a professional gymnast, and was part of the Greek national teams until the age of 19. However, as gymnasts are often unable to continue their profession throughout their lives, she needed to find a career elsewhere. "I was missing that aspect of my life a lot, so I wanted to carry some of the physical elements into my next occupation and do something where I could still be active and outdoors. Archaeology was a good match in that respect. Even now, working out in the field is one of the things that I love the most. And actually, many archaeologists enjoy the sensory experience of our work. We touch things with our hands – the soil, the stones, the features we find in excavations – and this approach helps us interpret and connect with finds."

Once her career in archaeology was established, how did Anastasia end up in Cambridge?

It wasn't the path she originally saw herself taking. "I was brought up very close to the French educational system", she remembers. "I went to a French school, and French was the first foreign language I learned. I also spent time in Paris as a graduate student, so when I was considering doing a PhD in classical archaeology, going back to Paris seemed like the next logical step. But I changed my mind when I realised that my interests lay in the cultures of early Iron Age Greece, with a particular emphasis on the islands."

"Even at this stage, I was already interested in the relationship between insular Greece and mainland Greece in antiquity, and how their cultures might be different. And I realised that this type of enquiry was a very Cambridge thing. There's a particular school of thought in the Archaeology department and the Classics department here, born from research in the 1970s and 80s. They view classical material in a unique way with different methodologies and a very open theoretical debate. That really attracted me, and I applied to Cambridge hoping that being there would help me develop as a researcher and as a professional."

However, Anastasia also had her reservations about applying to Cambridge. "I come from a background where my parents are well educated, but I was the first member of my family to study abroad. I thought the application process would be intimidating, expensive and overly competitive. I was also worried about my English; I could speak French as well as my Greek, but my English was not at that level."

Although the decision wasn't linear, Anastasia resolved to give it a go. "I sat a very intensive course at the British Council in Greece to gain the second level of English proficiency, which was required back then in order to even apply. Looking back, I must've been quite determined that I wanted to study at Cambridge, because I did all that alongside a full-time job as a field archaeologist for the Ministry of Culture. I would work in the morning and study in the evening, everyday for nine months."

All Anastasia's hard work paid off, and she arrived at St John's College to begin her PhD in 2003. She soon found that the University met all her academic expectations, and she formed strong bonds with her cohort.

"I met a lot of great people from both the Classics and the Archaeology departments, and we had a very strong graduate community. We used to spend nearly all our summers visiting each other's projects in different countries. I'd go visit my friends working in Turkey or Anatolia or Egypt, and then they’d come to the Greek Islands and help me with my research. It was so lovely to participate in each other's projects."

Research aside, Anastasia fulfilled her desire for an active lifestyle through different kinds of sport and movement, which helped enrich her life.

"I rowed for a little bit, although it wasn't really my thing. I also continued doing gymnastics on a recreational level. But what I really remember enjoying was walking! I was part of a society at my College, formed by lots of people from across Europe – Italians, Germans, Danes – and we used to do very long walks every Sunday."

"Sometimes we would walk from St John's to Ely and go to the Cathedral to attend evensong, have a nice dinner or lunch, and then take the train back to Cambridge. We had lots of funny experiences doing that in the middle of winter. Sometimes we'd end up covered in mud right up to our knees because the river pathway is so muddy at that time of year, and other times it would be so dark that we’d have to navigate our way to the train station using the light of Ely cathedral!"

After spending time doing postdoctoral research in Berlin, Anastasia became a curator at the Fitzwilliam Museum in 2012. She's now responsible for the entire Greek, Roman and Cypriot collections, and launched a four-year research project entitled 'Being an Islander: Art and Identity of the large Mediterranean Islands' in 2018. I ask her what interests her most about the objects she works with, and why they are key to understanding history.

"Objects reveal cultural identities and cultural processes. I work a lot on the iconography of these objects, the way they are made, how they portray particular scenes, and their myths. But deep down in my heart, I'm really interested in understanding what these objects meant to ancient people. I want to know how they interacted with these things, and how the items transferred to different groups or locations as a result of war or invasions."

"The objects' histories can tell us about wider social histories and powerful historical moments. If you look at objects from that point of view and focus on more than just their appearance, you gain something very important."

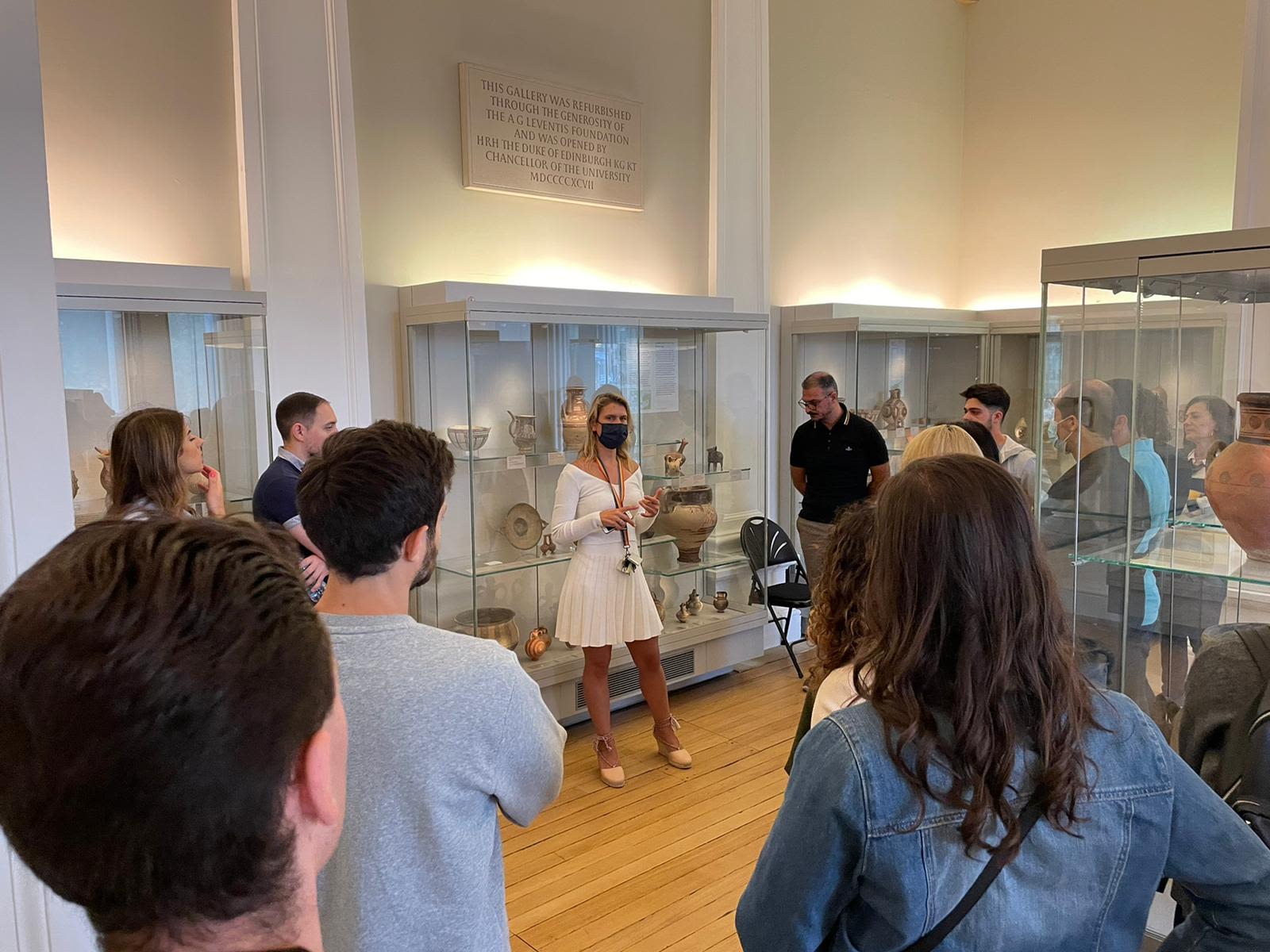

In her role as a curator at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

In her role as a curator at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Handling the loans from Sardinia during the installation of the Islanders exhibition.

Handling the loans from Sardinia during the installation of the Islanders exhibition.

Anastasia is also committed to engaging the range of different public audiences that the museum is open to. "I work with young adults, children and people with disabilities, and I have a special interest in LGBTQ+ groups. I’ve been working on a project that looks at material culture through a queer perspective for some time."

"I think it’s time we use powerful disciplines such as archaeology, classics, art history and material culture studies to allow groups in our community who have not traditionally been able to express their opinions and identities freely, to do so. Museums are very open places, but they operate historically from a white, heterosexual, privileged perspective. Now we need to let people from different cultures, like people of colour and members of the LGBTQ+ community, have their say, give their views, and reflect on their own personal stories. Rather than offering a strict learning process where we tell them what the objects are, we aim to let these people speak for themselves and tell us what these objects might mean to them."

There are some people who will not share Anastasia's passion for the importance of archaeology, material culture, and museums in today's world. I ask Anastasia how she would argue that her work on classical archaeology is relevant now.

"We are faced by this opinion quite often", she replies. "If I'm honest, it’s quite easy to prove archaeology’s relevance today. Some other disciplines might find it a bit harder, but that doesn't mean they're not worthy."

"Here's what I would say. In the aftermath of the Brexit referendum, I really started thinking: what is it that defines islanders? There was a lot of talk back then in the media, especially in the lead up to the referendum, about whether British culture is different to that of mainland Europe. A lot of these questions were about insularity. I thought that if we projected these discussions onto the past, we'd end up with a very nice set of research questions that we could use to gain a long-term perspective on current issues."

"And that's why we ended up with a project that deals with 4000 years of history. I wanted to interrogate a fundamental question: are island cultures different from mainland cultures? This is a question that affects millions of people in this country today as the result of Brexit, so it made sense that we should we talk about it from a historical perspective and see what we can learn from the past."

"Archaeology, history and other related disciplines don't just deal with the ancient past. They confront phenomena that still fundamentally influence our lives today."

Looking ahead, Anastasia has great plans for what's to come.

"Day-to-day I would like to continue finding ways of linking the amazing material we have at the Fitzwilliam museum with research and learning opportunities for students at the University."

"I'm also eager to create a very different project in the future, perhaps something that looks at the world of emotions in the ancient world, and how emotions have been depicted across a wider chronological spectrum."

For now though, you can find her at the Fitzwilliam — or at her favourite Cambridge pitstop, coffee in hand.

I ask Anastasia what her favourite café in town is, and her face lights up. "Oh, my favourite place is a little coffee shop called the Bould Brothers just opposite the Round Church! Every now and then if I need a little break on my own I go there for a coffee and sit outside, even if it's the middle of the winter. I love looking at the Round Church; I think it's a beautiful monument."

"It's also a very symbolic place for me because I did my PhD at St John's, so going back to that corner where I can see my old College brings back so many wonderful memories."

Dr Anastasia Christophilopoulou is Senior Assistant Keeper of Antiquities (Curator of Greece, Rome, Cyprus) at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. She is currently leading the 4-year research project ‘Being an Islander’: Art and Identity of the large Mediterranean Islands, (2019-2023) aiming to critically re-examine the concept of island life through material culture. The research project and culminating exhibition have been supported by the A. G. Leventis Foundation with a 5-year grant (2019-2021 and 2023-2024).

You can visit 'Islanders: The Making of the Mediterranean' at the Fitzwilliam Museum until 4 June 2023.